It’s a tricky balance, giving Moon Hunters a sense of random events without seeming repetitive.

“It’s my white whale!” declared Tanya X. Short of Kitfox Games, indie developer behind the mythology-based narrative game. “To some extent, it’s personal taste, but it also entails lots of attentive playtesting, and watching for how often someone chuckles or exclaims in surprise or gasps in realization.”

The game plucks encounters as if from a deck of cards, which runs the risk of feeling random and disconnected or repetitive. Finding that balance through testing helps with pacing, she said.

Moon Hunters is among several ambitious indie games with unusual narrative approaches in the IndieMEGABOOTH at Boston’s PAX East 2016.

Short strives to tell stories in Moon Hunters that gives players more agency in their choices of movement and encounters.

The player, she says, “is probably better at sensing what’s ‘too repetitive’ than the game’s generation algorithm – so giving them the means to seek out new content when they’re ready may be a smoother path than trying to force them into a linear set of encounters.”

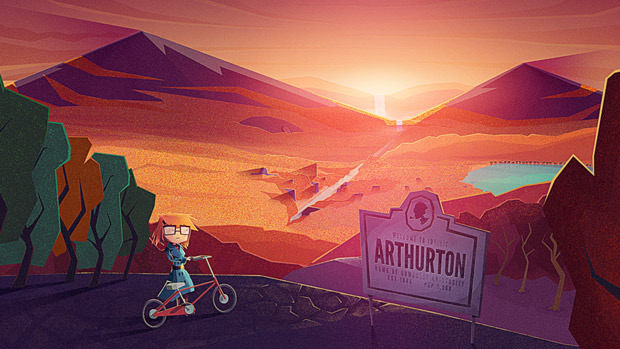

Joe Russ, a developer with Mografi who’s working on Jenny LeClue, comes from a background of animation, film, and interactive.

“I like solidly plotted narrative arcs, with a twist, of course,” he said. “I also enjoy hyper-stylized and more experimental narratives. Character studies are also pretty fascinating. I guess I like it all!”

Like Short, Russ seeks balance “between the kind of story you want to tell and leaving enough space and tools for the player to discover and explore that story without feeling force fed.”

For Jenny LeClue, Mografi’s first narrative game, the team’s experimenting with permanent narrative choices.

“We have this idea that everyone influences the story in the game: Jenny, the Author, the Player, and us, the Creators,” Russ said. “So we have this concept of social story choices. Since it’s three volumes, we can let players make choices that affect the way we write the next installment of the game, changing the story in a permanent way.”

Edward J. Douglas, creative director of Flying Helmet Games and the game Eon Altar, worked on titles such as Need For Speed and Bioware’s Mass Effect series as a cinematic designer.

“At the moment, I’m obsessed with the serialized episodic form used by Netflix and the like – how can you tell a compelling one-hour story that feels complete from an emotional arc standpoint, but leaves you hungry for more in the plot department?” he said. “I feel in games we’ve mastered this ‘one more level’ urge from a gameplay standpoint, and sometimes nail it from a story standpoint, but not always from the emotional arc standpoint. Maybe some have, but I haven’t! Always learning and growing.”

He noted the struggle of developing enough content to “create the illusion of choices resonant to the player.”

“This is where systems around emergent behavior are so great in creating unique experiences within a system, but this technique is seldom used on larger games that claim to be ‘story-driven,’” Douglas said. “This happens in part because the story will be something that ‘wraps around’ existing mechanics for a franchise or genre, rather than getting developed from the bottom up alongside game systems.”

As technologies mature to allow exploration of mechanics, he said, “we’ll be able to explore this a lot more across all tiers of the industry, including the AAA space. This exploration is one area where indie games have an advantage on AAA because they can take the kind of risks that a AAA game often won’t.”

“An allergy to exposition”

Short, the Moon Hunters dev, started writing short fiction in 2003, but got her start in interactive narrative design by making mods for Morrowind.

“I made a little cave where you could explore a half-underwater town of friendly draugh and mudcrabs, as I recall,” she said. “Later I would mod Morrowind more, to add a full quest-line in which you act as a servant-slash-spy in a new noble (and haunted) house.”

In narrative, she prefers to let players find their own way to the story instead of shoveling information at them.

“I have an allergy to exposition, possibly to my detriment,” she said. “I hate explaining anything, ever. I love letting the player (or reader) explore the narrative and find new layers of meaning, based on their own interest and understanding.”

In Moon Hunters, that’s made easier through non-player characters, interface elements, and encylopedias, she said.

Short’s a big fan of what Alexis Kennedy of Failbetter Games (Sunless Sea, Fallen London) calls “fires in the darkness.”

“The real world is structured this way to some degree, with individual people (characters) having their own motivations and opinions about what’s going on in the world (plot),” Short said. “This approach sometimes means that the connection between those ‘fires’ can be somewhat tenuous, if you’re not careful, but allows the player freedom in exploring and having a one-of-a-kind experience as a co-author.”

Russ, of Mografi’s Jenny LeClue team, doesn’t care for ham-handed exposition, either.

“I believe strongly in showing over telling,” he said. “Not that you can only show but, basically, don’t be lazy.”

He thinks games are great vehicles for letting the environment tell the story, which is “a solid tool to convey exposition.”

Sometimes the exposition must happen through dialogue, though. Then it’s on the writer to make it work.

“One approach I might use in writing expository dialogue is to have the characters multitask,” Russ said. “Say, create a silly or unrelated goal for the characters to be doing while also filling in the exposition. Say two kids are fighting over the last piece of pie at the dinner table while their parents try to explain how time travel works. It can help take the edge off what might be boring with a sort of fun-and-games element as well.”

Douglas, of Flying Helmet Games, established a rule for exposition on a recent game: “If the player only heard it, and didn’t see it or interact with it, presume they won’t remember it.”

That rule helped remind them it wasn’t always enough to just drop information into text or dialogue. “If we needed the player to remember it at a critical moment, we had to make it tangible,” Douglas said.

So they incorporated god entities – who wouldn’t become vital to the narrative until many hours into the game – into the art direction of the game.

“We designed very strong visuals around them, then used them all over the game – main menu screen, big landmarks in our early levels, branding, as well as in our intro video,” he said. “We also made lots of little ‘off-the-cuff’ mentions of them in dialogues connected to these visuals in the hopes that, when they did become a central part of the story, they would already be part of the players’ ‘mental landscape.’”

Agents of change

Russ admires the “story-first” approach of Oxenfree, which he played through in one sitting.

“It’s beautiful, and proof that story-focused games can be just as valid as very mechanic-heavy games,” he said.

He also enjoyed Limbo “for its ability to tell the tiniest, ambiguous, ambient story.” Russ said “it’s a reminder that narrative is a holistic experience and it can be applied like a fine mist or with the precision of a surgical scalpel. Both are valid and can produce interesting results.”

Douglas admired the work of the storytellers involved in Mass Effect 2.

“What I felt was brilliant in the writing of Mass Effect 2 was that rather than trying to pin the big moments of emotional change or decision on the player character…they abstracted it a layer down to your crew members,” he said. “The core of the game is a series of ‘episodes’ where you support a team member and then are the key ‘agent of change’ in their story, where you help them to resolve their own story.”

For Short, the globe-trotting adventure 80 Days was a narrative experience that truly left its mark on her.

“I was completely blown away by…its elegance and beautiful execution,” she said. “It’s very approachable in its format and aesthetic, yet has depth to keep you playing (reading) for many hours. For all that I love reading books, I often lose my patience with ‘visual novel’-type games with long passages, but 80 Days was one that kept me riveted, so that I was hanging on every word, curious how each character I found would return later in my journey.”

Short considers the game a landmark in game storytelling, calling it “probably the purest example of what narrative design is, at its core – shaping a dramatic player experience, by collaborating with the player directly.”

Boundless narrative opportunities

No matter whether storylines are branching or linear, Russ thinks computer games are a vital medium for narrative experiences.

“Even in very tightly controlled linear stories, players still have to move through the space and trigger events,” he said. “At the most basic level, they are part of the world, and they are causing the story to happen. And that’s so satisfying as a player, and so exciting as a creator!”

Douglas thinks the player’s power as an “agent of change” makes video games so perfect for sharing stories.

“The interactive medium is the only form of consumable art where the user is the agent of change of that experience, even to the point of changing the face of that world through their actions,” he said. “The opportunities for meaningful experiences seem boundless.”

Short just thinks we’ve all got insatiable appetites for stories from all around us.

“Humans love stories so much, I think they would be keen to tell and hear stories with just about any medium,” she said. “Computer, charcoal, dice, the bones of birds – we’re a species that thrives on patterns, learning, and communicating.”

As an example, she talks about her 4-year-old nephew, who already interrupts his father’s stories to suggest new paths and outcomes.

“Computers are really just a shortcut to support this, allowing more interactivity than ever before, with the listener having a participatory role in living out the story, making decisions, or even forming new worlds – not just in thought, but in an artifact that can then be shared with others.”

Wes Platt is the lead writer/designer for Prologue Games, a neighbor in the PAX East 2016 IndieMEGABOOTH. Their first game, an episodic narrative adventure called Knee Deep, launched its final act on Steam in March. Before that, he was a professional journalist for the St. Petersburg Times and Durham’s Herald-Sun. He designed collaborative real-time adventures at OtherSpace, Chiaroscuro, and Necromundus for players at jointhesaga.com. He also worked as a design lead on Fallen Earth, a post-apocalyptic MMORPG, from 2006-2010.