Sometimes I think I should’ve stopped OtherSpace after the first five story arcs.

So far, between 1998 and 2015, we:

- Kidnapped players to fight in an ancient war between two alien races and save a little boy in 2650.

- Toppled a pirate king.

- Overthrew a dictator.

- Shook up the Stellar Consortium government.

- Collapsed the Nall matriarchy.

- Blew up the Mystic homeworld.

- Invaded the Orion Arm of the Milky Way galaxy not just once, but three times.

- Loaded the entire playerbase onto the Sanctuary colony vessel and fled to Hiverspace for six months.

- Came back to the year 3000, to a much different Orion Arm.

- Wrecked Earth with a bunch of meganukes.

- Let a megalomaniacal player kill his own planet, La Terre.

- Collapsed the Nall patriarchy.

- Blew up Sanctuary/Concordance Station.

- Nearly tore reality apart with time-space rifts caused by the boy from our original story arc, grown into a psi-powered man now.

- Abandoned the Orion Arm in favor of the realm once known as Hiverspace, now called the Ancient Expanse.

- Toppled another pirate king.

- Overthrew another dictator.

- Shook up various planetary governments.

- Blew up the Galaxy Galleria space mall.

- Tinkered with time travel.

- Hunted clones of a favorite NPC villain.

- Killed the sentient starship Comorro after she gave birth to a baby Yaralu.

- Stopped an inhabited asteroid from pummeling a civilized world.

- Invaded the Ancient Expanse not just once, but three times.

And that’s just a sampling of “big picture” events. It doesn’t come close to capturing all the smaller activities that generated in-game news about what players have done – things that made them heroes, rogues, outright villains, or corpses. But you can see that some things – like collapsing power structures, alien invasions, and exploding planets (or space malls) – are a little too common.

Some veteran players caught in the thick of all this ongoing chaos complained – sometimes with justification – about fatigue from too much change too fast. New players coming to an original-theme game – already a challenge to grasp – also had to incorporate the accretion of actions and consequences that added layer after layer of narrative sediment to the back story.

So, if I’d stopped after five story arcs, it wouldn’t have grown so complicated and repetitious. We only would’ve had one alien invasion and we could’ve ended the game with the players escaping aboard Sanctuary. And OtherSpace would’ve been online for two years, instead of 17 (and counting).

Thing is, with players coming and going, it mostly proved repetitious for staffers running events and participants who’d been around from the beginning (or close to it). Some players, either weary of change or pulled away by the demands of real-life responsibilities, faded from the scene. New players took their place, though, and didn’t they deserve the opportunity to have the same sorts of experiences as those in the past? Shouldn’t they get a chance to topple regimes and fight off enemy invaders? Maybe even become invaders themselves?

OtherSpace kept chugging along with new story arcs. And then MMORPGs like World of Warcraft and EVE Online came along, drew players away. And smartphones grew prominent, without much appeal for online text-based gaming. And Microsoft, in its infinite wisdom, decided to disable Telnet by default in Windows – thus making it virtually impossible to discover a MUD on accident.

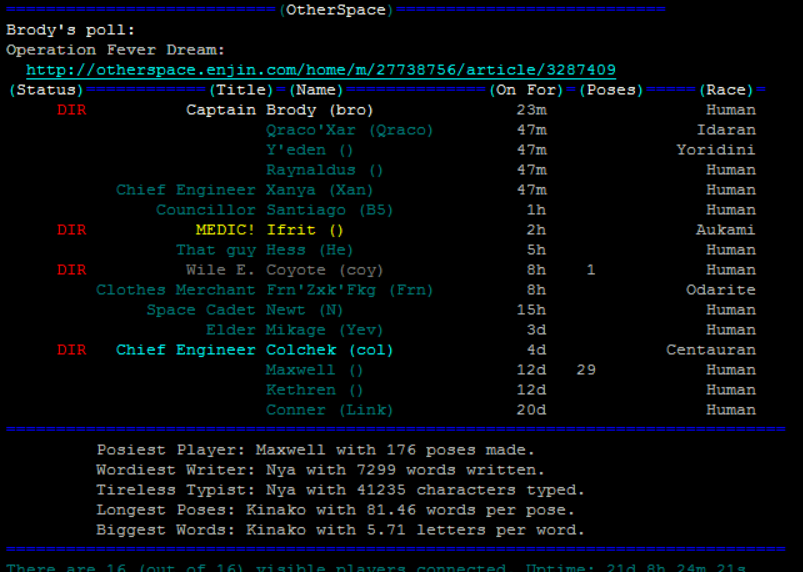

On our best days in 2002, we could boast more than 100 players online at peak times on the weekend. Now? A really good day is around 20 at peak. Of those, maybe half actually participate in activities on the grid. The rest linger to socialize out of character or they’re one of a handful of staffers like me.

It’s not all bad, though. With a crowd this small, it’s a lot more intimate and I’m able to connect more with the participating players. And that made me nostalgic for the earliest days of OtherSpace, when we first started in 1998 with a skeleton of a space opera theme and lots of blank narrative canvas for players to fill.

If we’re on the downward slide to ultimately ending OtherSpace, I figured, why not shake the Etch-A-Sketch one last time? Maybe all we’ve got left is a couple of years. Why not go back to the way it was, with the critical change of eliminating that first alien invasion and doing away with the Sanctuary storyline?

So that’s what we’re doing in June 2015. We’re taking the game back to the year 2650 in the Orion Arm, with humans living among felinoid Demarians, the bear-like Castori, the insectoid Odarites, and the bloodthirsty reptiloid Nall – among many others.

But I don’t think it’ll be enough just to offer the simplified original theme. I must apply some key lessons I’ve taken away from running OtherSpace for nearly two decades. They’re lessons any MUD developer should consider.

More player agency is better

Ultimately, the game’s not about you as the creator. It’s about the people who bring their imaginations and creativity to contribute to the story. Find ways to reward them for taking the initiative to build their own player teams and encourage them to take chances that can lead to legendary adventures. Let them gloriously succeed, spectacularly fail, or strategically retreat. Those are the moments that players talk about years later with misty-eyed nostalgia – not so much the time you stomped their sand castle with another alien invasion.

Shorter events trump marathons

We earned a reputation for events that lasted entire days. This was especially true for major combat-related events, with our tabletop-style referee oversight of in-game automated dice rolls. But all the other distractions that have come along since the 1990s mean shorter attention spans all around. I’ve got a toddler now. My real-life job is developing adventure games like Knee Deep. I can’t spend a day playing NPCs or reffing huge battles. The focus should be on shorter, quick-burst experiences that expand characters, build lore, and grow the narrative. That doesn’t mean no combat. It may mean changing how combat works, moving toward an RPI-style that’s automated and doesn’t require a referee.

Give them reasons to explore

A big hazard of a game built around the idea of scattered worlds (or broad fantasy kingdoms or big cities with sprawling grids) is that players can fall into ruts. Give them a starship, maybe they just sit in the cockpit and idle for hours at a time. Make sure they’ve got motivation to journey out among the stars, maybe even happen on other players in their travels. That could come in the form of cargo runs, passenger hauling, or even the promise of fame and fortune by hunting for undiscovered worlds and artifacts of lost civilizations. I’m really drawn to the premise of the upcoming No Man’s Sky game because it offers the potential of billions of worlds to chart and explore. For games that encourage exploration, especially those driven by database technology, it should be relatively academic to set up algorithms to randomly generate new locations for players to discover in their travels.

Make the world more dangerous

This goes hand-in-hand with giving players more agency. Basically, give them risks so that they’re more personally invested in the characters they create. Show them that some actions can lead to disastrous consequences. Games like OtherSpace already have permadeath – when your character dies, they’re dead. No respawn, no corpse run to retrieve your gear, no chance for vengeance. That story ends. Time for a new one to begin. But the risk of death just around the corner hasn’t always been apparent on OtherSpace, except in rough-and-tumble places like the criminal underworld of Tomin Kora. This might mean switching off the safety on your world, giving up control of the dice, and putting more automated threats into the mix.

Get out of the way

I think it was important that I put so much energy into the first major story arcs on OtherSpace back in the late 1990s. Those narratives helped build the lore and let the first wave of players put their fingerprints all over the game’s foundations.

But it’s annoying for players when you keep kicking their sand castles. After a while, it can feel like you’re shaking things up for your own amusement, even if you might have noble intent – trying to keep players on their toes, making the world interesting and vital, and discouraging them from staying away too long.

Ultimately, it’s beneficial to let players drive their own narratives forward. Give them NPCs to strive against, which can lead to epic showdowns, but also make it possible – even appealing – for them to strive against other players. Let their conflicts and alliances do more to shape the story.

As I said before, it’s not about you as a creator. It all comes back to the players who really give life to the world you’ve created. If sand castles need kicking or an Etch-A-Sketch needs shaking, whenever possible, let them do it.

Brody is best known for his work as creator of OtherSpace at jointhesaga.com. He’s also developed several other MU*s in the past, including Chiaroscuro, Necromundus, and Star Wars: Reach of the Empire. He’s been a professional journalist, but left that field to work on computer games such as Fallen Earth and the “Knee Deep” swamp noir adventure at kneedeepgame.com.